The Dough Nub: bringing the choice before us into sharp relief

It feels like things just may be coming to a head. I say this hesitantly, as it is not the first time. The financial crisis and the pandemic, the Paris Agreement and the IPCC reports, apocalyptic weather on every continent, all have felt as if they may presage fundamental change – but still we wait.

The sensation this time has been stimulated by a series of items in the media about Kate Raworth and Doughnut Economics: partly because it feels a sign that her work is getting greater traction, yet perhaps more so because of the nature and consistency of the response to that work and what that tells us.

In recent weeks, Raworth has featured on Radio 4’s Start the Week, with fellow guests Bernie Sanders and the Financial Times’ Martin Wolf. She was the subject of a 5000 word essay titled “the planet’s economist” in The Guardian’s Long Read series and, most recently, Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart dedicated an episode of their Leading podcast to an interview with her.

Martin Wolf acknowledged the attraction of much of what Raworth espouses but argued the only way of introducing it would be through “a global dictatorship”. Without that, he maintained, the transfer of resources from the rich world to the poor, “will never happen”. The Guardian piece quoted economist Branko Milanović arguing it is implausible that people in richer countries would ever vote for low or no growth: “Short of magic, this is not going to happen,” he says. Campbell and Stewart both recognised the attractiveness of Doughnut Economics, but neither could conceive how it could possibly be embraced by modern day politics.

In other words, well informed, reasonably intelligent, and not unsympathetic men did not dismiss the underlying urgency of the situation which her proposals seek to address. They did not identify technical flaws in Raworth’s economic arguments. They did not attempt to offer an alternative solution. All each could offer in response was the self-fulfilling ‘this will never happen because it will never happen’, apparently content to predict that humanity will choose to persist in destroying the ecosystems which have sustained us for millennia, rather than giving up the consumerist dream that has seduced us over the last few decades. They seem more comfortable residing in their dystopian wisdom than exerting themselves to advocate for Raworth’s vision.

This is depressing both because of the seeming untroubled acceptance that humanity is not capable of being roused from its lassitude, even in the shadow of such horror, and due to the prospect this may prove correct. It also though reinforces the sense both that, in the absence of other alternative visions, Doughnut Economics is worth investing in all the more, and that, as it is only human inclination and not some scientific absolute or natural law preventing us making Doughnut Economics a reality, it is still within our collective gift to make it happen.

Understandably, perhaps, this pattern is repeated across the economy and society – including within the legal profession - as some are ignorant of the existence of Doughnut Economics; some reject it out of hand as beyond their narrow contemplation of how the world is; some think it is hopelessly optimistic; and some are desperate to see it become a reality.

I was fortunate to be among some of the last of these groups when, in March, Raworth was the keynote speaker at the annual summit of the Global Alliance of Impact Lawyers, held in London. There, despite a tube strike, there was standing room only as she challenged her audience to contemplate how the law and the legal profession could contribute to creating an economy that is regenerative and distributive by design. Happily, there are already many initiatives that align with that aim, including the Better Business Act levelling the playing field for purpose led businesses, relational contracting, initiatives bringing stronger stakeholder voice in governance and the Equality Impact Investing Project equalising power dynamics in finance.

Consistent with the reservations of Martin Wolf and the rest, the issue is not that legal interventions do not exist and are not credible. It is they need to be embraced as standard practice and for that to happen the conversation between client and advisor needs a fundamental shift too. And that takes us straight back into the challenge that we all, lawyers and non lawyers alike, face. How do we fundamentally change what we rely upon for our day to day existence and, in particular, get enough of us voluntarily to do this together whilst still dependent upon it? As lawyers how can we expect clients to pay us for offering advice (unless they actively want this themselves) which is in the public interest as much as their own? How can we lead in this, rather than following only when clients have themselves first embraced that change? How can we expect clients to ask this of us, if they do not know what we can offer? If we are waiting for others to move first, can we really look future generations in the eye when the historic record shows this was the decade more than any other when we failed to act when it mattered - future generations include our younger colleagues practising today?

The regulator of solicitors in the UK, the SRA, is currently consulting on its three year strategy to 2026. Its professed mission is to support public confidence in legal services and the sector as a whole. What this means in times of such uncertainty, with so much shifting so quickly is hard for any of us to know definitively. However, it is reasonable to assume anything which tries to ignore that turbid environment we are practising in will be inadequate. At the very least, the SRA should be very explicit that if individual solicitors and firms wish to be at the forefront of the changes we need to see, then (save in limited examples which may involve them running foul of other professional duties and principles) they may do so without fear of regulatory censure. It might be asking too much for the legal profession to take the lead on its own when politicians, financiers, other business leaders and professional service providers are not doing so, but not asking enough of the lawyers is equally problematic.

Even with this permissive approach, acting on this rigorously will not be easy: indeed, it will probably be too much for most legal practices in their current form. A business model which is predicated on ‘growing the pie’ each year, so that more partners can be promoted but all partners make yet more money is fundamentally incompatible with the principle of humanity providing a social foundation for every one of us whilst living within planetary boundaries. It takes us back to the predictions of Wolf et al, that lawyers will never accept the reduced salaries and drawings that would likely flow from exercising more discretion in the sort of matters they chose to advise upon: the sort of change that would be the profession’s best contribution to GHG emissions reducing at the speed and scale necessary to limit (or return) global temperature increases to 1.5°C. And this is why I feel like things may be coming to a head. Whether it is economic commentators or partners of law firms, it is becoming harder to resist the sort of changes we need to see – and which do not have any credible alternatives in terms of staving off climate and biodiversity catastrophe – without admitting the reason for not embracing them is selfishness and greed. Traits shared by most of our peers, but inexcusable nonetheless in the face of their implications.

Maybe the time is ripe for the next generation of law firms: ones with flatter structures, much more flexible working, and more effective use of technology. They could combine the energy and passion of youth with the wise heads of some of the senior lawyers today, who have the luxury of not needing to still be paying off mortgages and school fees and can focus on using their contacts and experience to provide some leads and guidance to their young colleagues. And they could combine paying decent but not exorbitant salaries with allowing staff to derive meaning and purpose from their work – not the Faustian pact epitomised by the deal offered by US firms in the City: eye-watering wages for heart-shrivelling work.

The likes of GAIL, Legal Voices for the Future, Charter 1.5 and the Bates Wells’ Pledge are showing what is possible today in legal practice. Tomorrow promises another level of progress entirely. It will require the imagination, resolve and narrative genius of a Kate Raworth to make it real, but there are individuals in those organisations and networks displaying some of those traits already. We must not let the besuited naysayers deter them.

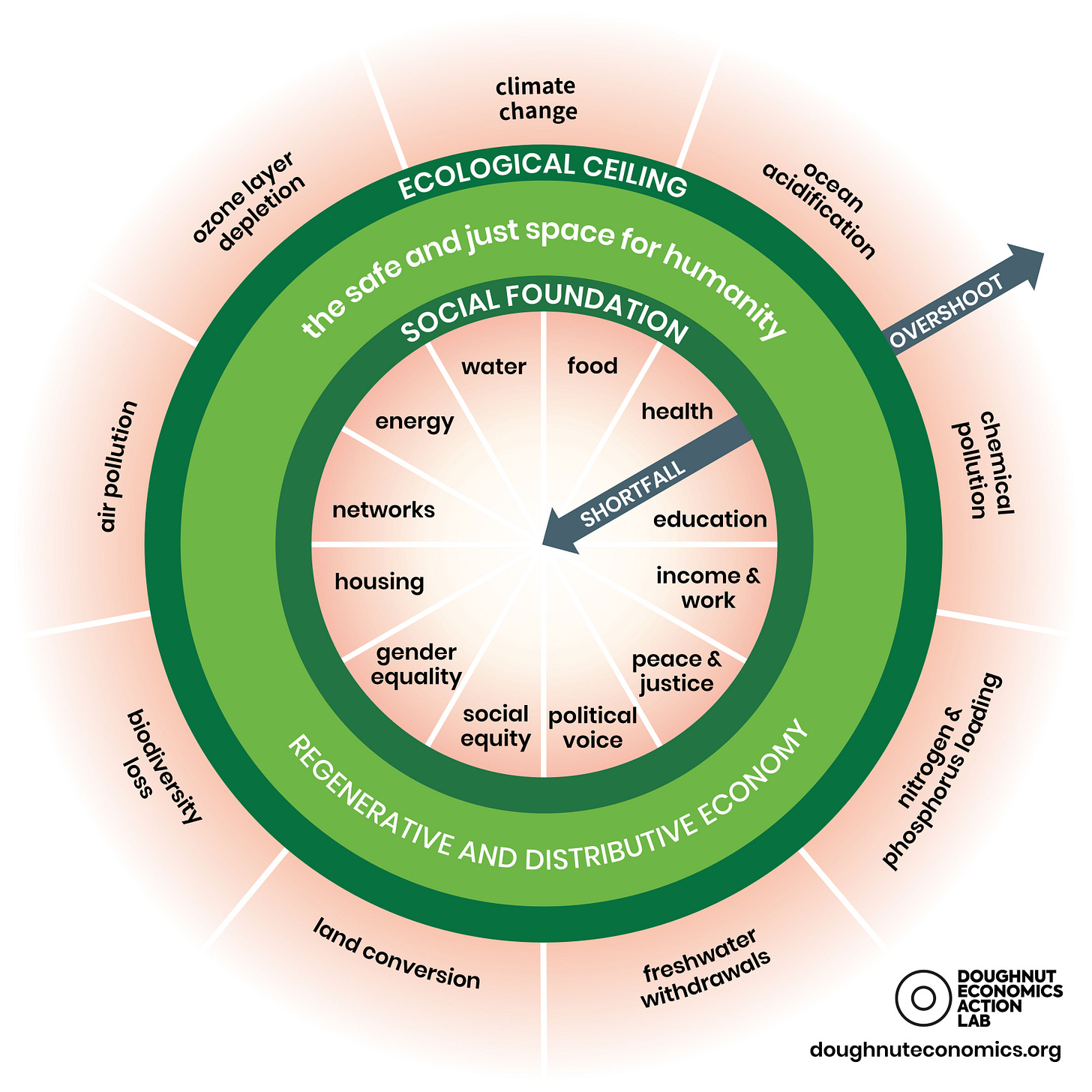

Image Title: The Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries.

Credit: Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier. CC-BY-SA 4.0

Citation: Raworth, K. (2017), Doughnut Economics: seven ways to think like a 21st century economist. London: Penguin Random House.