Ubuntu

The Uncertain Solicitor on Shifting Mindsets

In this series of posts, I have touched on the challenges posed by time (how we have run out of it) and truth (how hard it is to face up to it). Here I want to focus on an even more sensitive issue, one which forces us to confront the possibility that we – and specifically our reluctance to embrace new ways of looking at things – may prove our own worst enemy and be the cause of our own undoing.

There seems to be disagreement over whether or not it was Einstein who said, "we cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.". Whomever the source, it intuitively makes sense, but how do we think differently? If it was as simple as deciding to do so, we would presumably have done it already, given what we know about our situation.

The reality is there is no shortage of different thinking. There is Kate Raworth balancing the achievement of a social foundation for all whilst operating within our planetary limits and Mariana Mazzucato demonstrating the contribution of the public sector to innovation. There is Elinor Ostrom debunking the myth of the tragedy of the commons and Robin Wall Kimmerer teasing out the reciprocity of our relationships with the natural world. There is Donella Meadows guiding us through the complexities of systems thinking and Rebecca Solnit and Joanna Macy managing to locate active hope and unfolding possibilities in the face of the challenges before us. Nothing I reference here is new. This is not about taking a contrary position for the sake of doing so. It is about recognising that a refusal to be open to new approaches and clinging to business as usual is the surest way for us to fail.

Even if we make the effort ourselves to think differently, how do we instil a collective embrace of new ways of looking at things? Identifying how we trigger the motivation to haul ourselves out of the logic that has led us here seems perhaps to be the biggest prize of all.

Thinking Differently

Maybe it would help if we could end our fixation with seeing everything in proprietorial terms: my client, my firm, my following. It seems fanciful, applying current thinking, to do anything else. But the cumulative effect of one hundred thousand solicitors in England and Wales all adopting that approach is a fragmented and febrile professional culture. It means we regard acting in our client’s interests as promoting positions which push risk onto others, immediately setting them in opposition to those they want to do business with. I catch myself doing this instinctively. You almost have to when presented with a contract that is seeking to do that to your client. You push back and the legal costs mount and the relationship between the clients sours before it has begun as old arguments over warranties and indemnities and liability caps are rehearsed again.

What if we created the conditions to let go of this thinking? What if we talked to our clients about embracing the African philosophy of ubuntu: I am because we are? What if our focus was on the collective wellbeing deriving from our work, if that was how our clients’ success and our own was measured, and if that nourished a sense of worth built on intrinsic values, rather than size of bonus or progress up the slippery pole?

It could be more powerful yet if allied with another piece of old wisdom which seems worth revisiting. Gandhi asserted that Earth is able to provide for humanity’s needs, but not its greed. That remains true today, we are told: it still could provide for the billions of us inhabiting the planet. It is in our gift to ensure that all of humanity has their basic needs met, without exceeding our planetary boundaries PROVIDED THAT[1] we place restrictions on the extent to which individuals, or corporations, or nations cause greenhouse gas emissions, or pollute our natural commons, or plunder our natural resources. Can we prioritise working with clients committed to delivering on this objective? Can we show them how it may be achieved using existing and new legal instruments for mutual benefit?

Let’s take, for example, a re-evaluation of the concept of fiduciary duty. Modern portfolio theory argues that prudent investment practice is to diversify your holdings. The largest investors (the sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, insurance companies) and the investment managers that work for them are effectively invested in the market as a whole. Even if there is an apparent short term financial gain by investing in high emitting and environmentally destructive companies who externalise costs onto third parties, where this exacerbates climate breakdown and the sixth mass extinction, these are harmful to their beneficiaries’ interests when viewed through a systemic, long term lens (which is what these investors need to be adopting, assuming their aspiration is to stick around). So the current thinking of chasing short term gains each quarter begins to look like a breach of fiduciary duty. The duty might instead be met through different thinking such as looking at the wider impacts of the investments and the interests of beneficiaries each taken as a whole; in other words applying a holistic perspective not an atomised view of each investment individually and only in relation to financial metrics. If this is right, it should be the approach applied across the whole financial system and suddenly ESG and sustainability are not niche products, but the default requirements for investment.

This can also align with the fiduciary duty of directors. If their duty is to run their company for the benefit of its members and those members (such as the large investors) need the company not to externalise their costs or contribute to climate breakdown and ecological destruction, the directors better not perpetuate that current practice if they want to be sure they will not be at risk of members applying different thinking and challenging them for breach of fiduciary duty before too long. And this is not something unique to listed companies only. All companies are interdependent on their stakeholders: they are part of supply chains and depend on supply chains; they cannot exist in isolation of customers and employees, of the environment and physical and social infrastructures. Ultimately, directors’ decision making must take account of this and they need to be advised to recognise it. I am because we are.

And then there is the solicitor’s fiduciary duty of course. Not only do we need to be alive to the need to consider the changing nature of fiduciary duty as it applies to our clients, we need to reconsider our own. Where we believe or suspect the matter we have been invited to advise on will cause material and foreseeable harm to third parties, what is our overriding duty if we know that harm will adversely affect other clients of ours and the public interest (and may even not be in the long term interest of the client itself)? In other words, fiduciary duty involves taking into account our interdependence and reflecting that in how we practise our profession for the benefit of our clients. I am because we are.

Behaving Differently

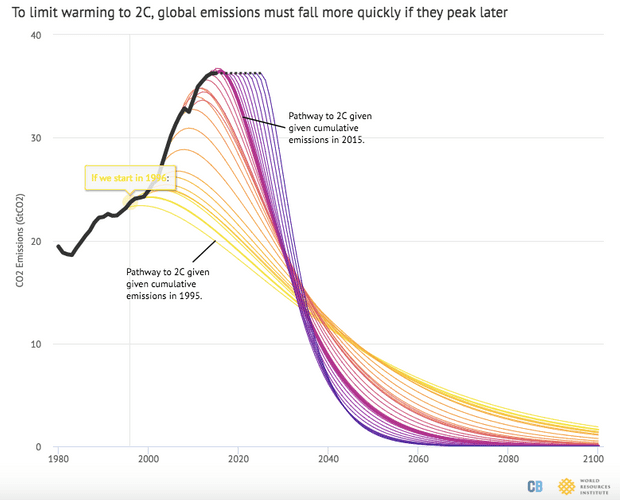

Fig 1

We must restrict increases in global temperatures to no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. To do this, the IPCC tell us we need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 45% from 2019 levels by 2030. Fig 1 reminds us of the scale of the change this demands and it is clear from this that the goal is only achievable in these timescales by generating significantly less emissions. Alien as it may feel applying ‘current thinking’, we need to introduce some red lines to cease certain activities which work against our 1.5°C aspiration and those which are clearly inconsistent with emissions reduction this decade at the scale required is an obvious place to start.

Some governments are introducing red lines of their own, (whether the Dutch capping the number of flights from Schiphol Airport[2], the French introducing measures to counter planned obsolescence[3], or the UK announcing a ban on the sale of petrol and diesel cars from 2030[4]). However, for the most part, we cannot wait for legislation to drive the changes we need and we have to take the initiative, whether as individuals, individual businesses, or individual industries, to encourage others to do the same.

In some circumstances it may be difficult to determine on the basis of an individual case, whether or not its impact is consistent with the 1.5°C aspiration. In many cases it will be clear though, so let’s begin with those. The International Energy Agency says that there must be no new development of oil and gas, partly because there is already more than enough in the system to use up the remaining carbon budget and partly because there are huge opportunities from focusing instead on clean energy sources. So, a simple red line: let’s not assist with our professional advice the development of, or financing of, or lobbying for, or subsidising of new oil and gas fields.

Then there are things like deep sea mining activities; deforestation; industrial-scale, chemical-dependent agriculture; transportation projects which will increase fossil fuel use and dependency. I have heard ‘current thinking’ argue that turning away from these would harm developing nations and it is inequitable to penalise them so we should carry on. That feels to me both hypocritical and disingenuous. It is not a case motivated by protection of the right of those nations to have what we have: we want them to pursue these activities partly as cover for us also to do so, and partly because we benefit from them, consuming what is produced and providing finance for it at inflated rates of return.

Different thinking would involve red lines around those harmful activities, but also the provision of the expertise and the capital to help such nations develop their own clean energy and nature friendly solutions. The latter should be at 0% interest, by the way, because (i) we have the surplus capital lying around anyway and (ii) it will do us more good in the long run than using it to contribute to driving global temperatures above 1.5°C all for the sake of preserving expectations of acceptable IRR – something which, the more relentlessly it is pursued, the more meaningless it will ultimately become.

Just Transformation

There is much talk of a just transition. Justice must be at the heart of what we do and represents different thinking in and of itself, given how absent it has been from the practices that have led us here. If we are honest, we have missed the boat for transition. Only transformation will suffice, in light of the IPCC assessment. It is clear we need not only to use less carbon intensive forms of energy, but to use less energy period. To achieve that justly, it is also clear that some parts of the world need to reduce significantly their per person consumption levels as we rebalance those emissions per head numbers.

The World Inequality Database has established that 10% of the world’s population are responsible for about half of all greenhouse gas emissions, while the bottom half contributes just 12%. Meanwhile the effects of climate heating are already, and will continue to be, disproportionately borne by those generating the least emissions.

Most of us genuinely believe our lifestyles are not excessive. We cannot associate the luxuries we enjoy with the misery others experience, even when the greatest scientific minds of our generation spell out the connection for us. As solicitors maybe we could start by declining to act on matters involving the production, sale and purchase and use of items like super yachts and private jets and work backwards to the likes of SUVs and similar casual unnecessary extravagances, whilst looking for ways to support greater investment in public transit systems and healthier local mobility options like electric bikes and scooters. These may seem relatively small matters of themselves, but which can communicate a lot about changing attitudes and priorities.

What is the more radical stance: to turn away a rich client wanting to do things which will burn a load more carbon for their personal benefit, or to facilitate practises and lifestyles we know will cause misery and death to swathes of humanity? Current thinking and different thinking may give us alternative answers. I know which I feel more comfortable with.

New developments

Current thinking may make arguments in response to what I have suggested here like ‘all clients are entitled to advice’ (caveat: if they can pay); ‘we cannot be sure the foreseeable harm can be attributed accurately to any particular claimant’ (law and science have not caught up yet with the situation we are in, so it is ok to carry on for now); or this foreseeable harm might avoid some other possible foreseeable harm (definitely very bad is ok if there might be something even worse happening). In this emergency such arguments don’t hold water. Hopefully the current Australian case of Woodside Energy will help expose this as such.

Woodside is seeking to develop a new gas field off the west coast of Australia which, even by its own estimates, will generate 878million tonnes of carbon – easily over 50% more than the entire annual emissions of Australia. It is subject to a legal challenge using attribution science to demonstrate these emissions will contribute directly to destruction of the Great Barrier Reef, thus seeking to establish a causal link between these emissions, rising temperatures and coral bleaching.

If the challenge succeeds, it will show the law and science are catching up with our reality. Even if it does not, it forces us to re-evaluate our work. Would you want to advise on a matter you know will contribute massively to humanity failing to meet its ambition of holding temperatures below 1.5°C? How would you feel, knowing the consequences for vast numbers of living beings across the planet? How do you think your justifications for doing so will sound in ten or twenty years’ time? We might have pleaded ignorance (possibly) in 2002: we cannot now.

We can no longer adopt an amoral position because to do so is itself taking a position which has foreseeable adverse consequences. A quick flick across the websites of a random selection of international commercial law firms indicates a universal desire to present as sustainable and responsible businesses. To be so we need to employ different thinking, such as working out how to make the sort of legal support we provide and promote as part of CSR or pro bono initiatives – the sort of thing those involved are often most proud of and keen to refer to when asked about their work – part of our core offering and not an incidental form of penance. Doing something like this, alongside establishing our red lines, holding them and making them more robust as we go, does mean change and challenge. It may also mean more rewarding and valuable work: different, but good.

It may be completely different thinking to that I have described here which prevails and saves the day. I will be fine with that if a just transformation is delivered. It is carrying on doing the same thing and expecting a different outcome, or (worse) not caring whether there is a different outcome, that will be unforgivable.

Postscript: I found this really hard to write – so much to say which is complicated in itself, never mind the interconnections, and in so little space. If you have got this far, thank you for persevering and I hope if you are feeling a little uncomfortable and/or dissatisfied that more questions have been raised than solutions, I hope you may acknowledge that at least is a reflection of where we are generally, but that asking the questions is preferable to not doing so. Next time, however, I will make a stab at looking at one way of trying to build solutions from where we are – applying the Three Horizons framework to the challenges we face. I hope you will return for that.

[1] (old habits do die hard)

[2] https://www.climatechangenews.com/2022/06/27/dutch-government-issues-world-first-cap-on-flights-from-european-hub/?utm_source=Climate+Weekly&utm_campaign=f1fd8aaaa2-CW-1-Jul&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_bf939f9418-f1fd8aaaa2-407991717

[3] https://buymeonce.com/blogs/articles-tips/interview-france-fight-planned-obsolescence

[4] https://www.driving.co.uk/car-clinic/advice/2030-petrol-diesel-car-ban-12-things-need-know/